MUST WATCH

(CNN)Kevin Macdonald has carved a career out of telling the stories of extraordinary people, and ordinary people finding themselves in extraordinary situations. The Oscar-winning director behind "Touching the Void," "Whitney" and upcoming drama "The Mauritanian" does not do dull. So, on paper at least, making a documentary out of thousands of hours of people's home videos reads like a shift into a lower gear. That said, we live in interesting times.

In "Life in a Day 2020," Macdonald takes on the monumental task of summarizing what the world was up to on July 25, 2020. Two unfolding events dominated the news cycle, as

Black Lives Matters protests gripped the United States and a world in lockdown recorded

254,000 coronavirus cases. But those headlines are only a fraction of the story -- which is precisely the point of the film.

To craft a fuller picture, Macdonald and executive producer Ridley Scott asked the public to submit their own footage from July 25, just as they had done for the original "Life in a Day" in 2010, a feature cut together from 4,500 hours of home videos sent in from around the world.

"I plagiarized the idea from Humphrey Jennings, the great British documentary maker," Macdonald tells CNN. Jennings' 1942 film "Listen to Britain" recorded the lives of the public during World War II, telling their stories in their own words. At a time of great privation and upheaval, both the existential and the trivial emerge. Jennings teased out the personal from what could otherwise have been a sweeping metanarrative of Britain in wartime. A useful blueprint in 2010, "Listen to Britain" only became more relevant in a year consumed by the pandemic.

Macdonald's own social experiment received over 320,000 submissions this time, totaling some 15,000 hours -- over a year and half's worth of video. A team selected approximately 500 hours of footage for the director and his three editors, who whittled it down to 15 hours of "really amazing stuff," out of which they cut an 86-minute film.

"The quality of the material was so much higher (than in 2010)," he says, and "much more diverse," with submissions from 192 countries.

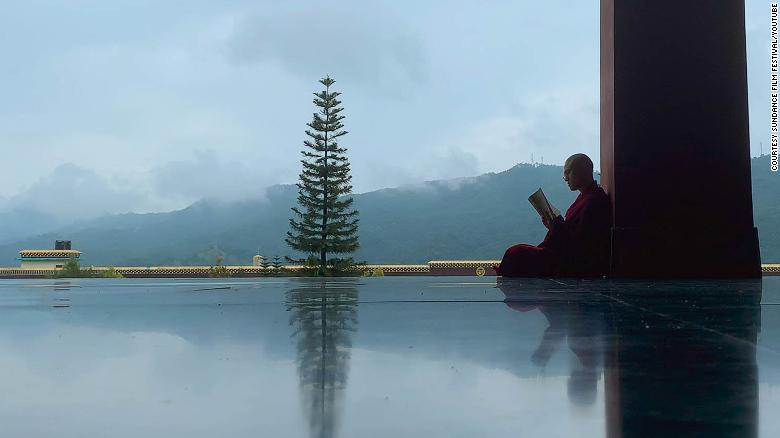

Structured as a microcosm of life itself, the film begins with birth and ends in old age. The pandemic weaves its way across the narrative, from high school graduations at home to footage of the AstraZeneca vaccine in development, but it never dominates. Common threads including love and rites of passage are combined into montages. Characters including an opera-singing doctor in Lagos, Nigeria, seize their moment to shine, while others, such as a big-dreaming Russian boy, come in and out of focus.

Tragedy and joy stand shoulder to shoulder, along with every other emotion, coexisting in all places at all times -- and it's the emotional resonance of the videos more than anything that unites the film's disparate parts.

"We are trying to tap into the subconscious of the world," says the director. "The trick of it is to make people feel like there is a story, even though in reality there isn't," he adds.

Some

critics have questioned whether the format has been outmoded by social media and new video platforms. If a documentary is made of the same composite parts, how does it remain distinct?

"The key thing is that it's curated," Macdonald says. "What makes it art, I think, is that it has an individual's point of view on it -- and that individual happens to be me. And if you disagree with my selection, or the emphasis I've given something, or the use of music, you know who to come to."

In an age when self-expression is dominated by social media and a story's reach is often dictated by algorithm, Macdonald argues there is value in plugging humans into the selection process. Social media presents "overwhelming quantity," he says, "I feel like I want a way to navigate through (it)." (There is an irony that the film is distributed by YouTube, where

over 500 hours of video are uploaded every minute.)

That said, the film doesn't ignore the impact of social media altogether, choosing to bundle influencers into a montage that stands in contrast with everything else. Their peculiar brand of online hyper-reality is presented almost as a curio: exhibit A of what Macdonald didn't ask for, but a part of today's reality nonetheless.

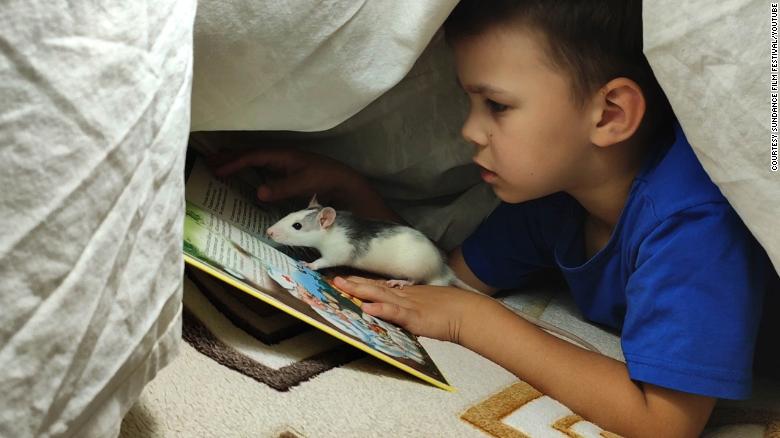

McDonald says he encouraged contributors "to forget about that and to try and film things honestly." We see a couple struggling to conceive a child, a failed marriage proposal and a sick man discussing his illness with a young girl -- life unvarnished, in other words. "I'm so grateful to those people," he adds. "They're braver than I am, to be able to actually show these things."

Behind all these testimonies is the same fundamental motivation that has driven humans to tell their stories since time immemorial -- one best expressed by a man called Semyon, filming himself in Northern Siberia. Alone in the wilderness, he tells the camera, "what I fear the most is that my life will pass unnoticed; that my name won't matter in the history of the world."

"He has the same impulse that so many people have," says Macdonald. "It's not about vanity ... It's, 'I want people to recognize that I'm here.'"

With no signs that humans will cease sharing their stories any time soon, the director may be granted his wish for a third edition of "Life in A Day" in 2030.

The world may look somewhat different then, but some things won't have changed. "So many people share the same basic fundamental fears, desires and loves," he says. "There is beauty in the everyday."