(CNN)For the first time since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, a majority of Americans believe our fight against the virus is getting better in a new Gallup national poll, the latest sign that optimism is creeping back into American life after a year of quarantining, mask-wearing and vaccine-waiting.

Six in 10 Americans said they think the Covid situation is getting better as compared to just 14% who said things were getting worse. (Another quarter of respondents said things were roughly the same.) That's a remarkable turnaround since even November, when almost three quarters of Americans (73%) said the Covid situation in the country was getting worse.

The relative optimism/pessimism about the virus over the past year has closely tracked with surges and declines in the number of cases in the country. That's true now, too; cases have been dropping steadily since mid-January, and with it, hospitalizations and deaths. As of Friday morning,

the United States is reporting 59,410 cases per day, the lowest rolling 7-day average since mid October.

But, unlike past declines -- only to be followed by even larger surges -- this moment appears to be different. There are now three authorized Covid-19 vaccines -- Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson -- and

80.5 million does have been administered in the United States. For the first time ever, the US is averaging more than 2 million vaccine shots administered a day over the last week.

Outside of the immediate realm of public health, the news is also good. The economy

added nearly 400,000 jobs in February while the unemployment rate ticked down slightly to 6.2%. (Worth noting: There are still

9.5 million fewer people with jobs than at this point one year ago.)

And, it's spring -- or almost spring! -- in most of the United States. Days are getting longer (and warmer).

All signs point to a justifiable optimism. And yet, I, for one, find myself continuing to wonder whether optimism (given what we've been through over the last year) is akin to

Charlie Brown convincing himself that this time he really is going to kick the football before Lucy pulls it away.

Amy Davidson Sorkin, writing in the most recent issue of the New Yorker

, touched on these fears of being optimistic:

"Optimism is one of the things that the coronavirus pandemic has made it hard to hold on to, or even to measure. Going through the data can have a seesawing effect on a person's state of mind...

"...Joy can be hard to come by, because of the weight of what the country is still going through. The average daily number of deaths is about two thousand—a sharp drop from mid-January, when it was well above three thousand, but quadruple what it was last July. And, as February ended, there seemed to be something of a wavering in the progress—perhaps because extreme weather caused disruptions or, more ominously, because of the spread of what appear to be more infectious variants."

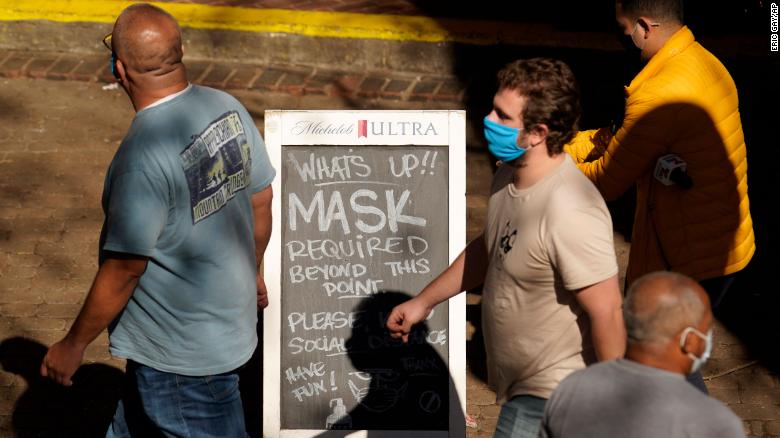

The variants, yes. And the decisions by governors in Texas and Mississippi -- contra every public health expert in the country --

to lift mask mandates. And the ongoing suspicion among a not-insignificant number of Americans about taking the vaccine at all. And, even more broadly, the sense that optimism over the past year has turned, time and again, into ash in our collective mouths. That in hoping, we are committing Icarus' sin -- flying too close to the sun and ensuring we will come crashing back to earth by yet another surge or a terrible new variant or, well, something else bad.

To be clear: Not everyone feels the same trepidation as I do. I am -- and have always been -- someone waiting for the other shoe to drop. A worrier. There are plenty of people who can take the good news around the declining case load and the rising number of vaccines at face value. Good news as good news.

But I also think that the cumulative effect of the fits and starts of our response to this virus as well as President Donald Trump's outlandish promises about when we would all be beyond it have combined to create a level of distrust of what we are seeing and being told -- even when it is good news.

Jonathan V. Last, writing in the Bulwark, put this phenomenon well in a

piece in late February:

"We are suffering from something like public health PTSD, where the happy-talk lies told to us during 2020 have made us unable to accept genuine good news in 2021...

"...If I were going to psychoanalyze America, I'd say that we were lied to for so long by people in positions of authority that we started reflexively taking the other side of every piece of good news on COVID and distrusting it. Because all of the previous 'good news' was flim-flam."

Yes, that. What Sorkin and Last hit on is something I have been thinking a lot about lately: Once the physical threat from Covid-19 killing us is significantly reduced -- maybe by the summer? -- how long will it take us to mentally re-adjust to not worrying about how every trip to the grocery store might be a mortal mistake? Or, more benignly, when might we hug people -- even when we are vaccinated again -- without thinking about whether it is the "safe" thing to do? Or walk right by people on the street, without bowing out to stay as far away from sharing their air as possible.

For the past year, we've been necessarily focused almost exclusively on stopping the physical ways the virus spreads. The mental piece of what it means to have fundamentally re-oriented our lives -- and the way we interact (or don't) with others -- has been a secondary (or lower) conversation. In these coming months, as we get closer to herd immunity and the physical threat the virus poses to us declines, how Covid-19 has changed how we think will be our biggest challenge.

Again,

Sorkin hits the right note: "One can, in the course of a long pandemic, begin to get used to too many intolerable things. But it would be disastrous to grow numb to hope."